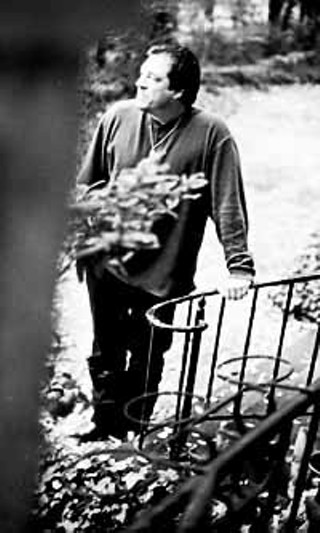

The Art of Being Dagoberto Gilb

What's He Got Against the Establishment?

By Clay Smith, Fri., March 23, 2001

It was one of those days when Dagoberto Gilb was about to start a scandal, and he needed some advice. Anyone could see that he was seething with anger. Lots of people get involved when he is this way; he gets mad at institutions. Gilb is a huge hulk of a man, barrel-chested, stout, and known for always, always saying what is on his mind. Ten years ago, when he was living in El Paso but happened to be in Austin, he wanted to get to the bottom of something that had been bothering him for some time. When he walked into the office of The Texas Observer, which had published some personal essays he had written, he was standing in front of a group of people who knew that when Dagoberto Gilb flips out, it's best to just get out of the way. "Who's the editor?" he barked. Gilb wanted to know his position on a matter that had been bothering him: Would it really ruin his writing career if he punched the editor of Texas Monthly in the face? Gilb said that he had written an article about gangs in El Paso for Texas Monthly and for a year the magazine hadn't published it, although Greg Curtis, who edited the magazine then, doesn't recall keeping the article that long. Gilb said they wouldn't return his phone calls and hadn't paid him the $1,500 they owed him. Gilb grew up fighting, but this time he was punching for keeps.

Many writers believe that the most interesting thing about them should be their writing, not themselves. It is sometimes a disaster when the same person wants to be a writer and a personality, but Gilb, though he can actually be quite shy, isn't a student of the wallflower school. After you've spent some time with him, it is easy to take his cue and begin laughing at all of your own jokes and to cuss in an uninhibited manner and to think that there are women lurking around every corner just itching to make their move on you. And you've never even been a bouncer at a sleazy biker joint like he has or a proud carpenter for 16 years or a janitor while you were a senior in high school or a professional laundry-sorter when you were even younger than that.

Even when he isn't angry, people cannot resist talking about Gilb. He just blurts out the kind of thing people keep to themselves. At a recent dinner party, the following memories, most from his recent book tour for his new collection of short stories, Woodcuts of Women, tumbled out of his mouth: one wealthy and beautiful Russian agent, one confused and apologetic undersecretary of state, 22 Chicano ghosts (one for every city he visited on the book tour because "everywhere I went there'd be a ghost of the Chicano past"), and the cold night a long time ago -- oh, it was so cold -- when he took his family camping in the Chaco Canyon and his teeth wouldn't stop chattering and he had to keep piling blankets on top of his children. Also, the time he was on a plane that wasn't full and he was "in a mood" because he was writing. His leg was cocked up on the armrest, which was clearly saying to people, "PLEASE DO NOT SIT HERE, ANYONE," and he was avoiding eye contact when he heard this tiny little voice say, "Is anyone sitting there?" He grimaced and looked up and it was, of course, a woman who has been on the cover of Playboy twice, thus forcing him to spill his papers into the air and all over himself.

His freshmen composition students at Southwest Texas State don't even know he's a writer because he doesn't tell them. He doesn't want his age in this article ("Why does my age have to be in it? Women don't have to say!"). And he is tired of people writing articles saying that he is girl-crazy. Here is why people have been writing articles saying he is girl-crazy: We were talking at Jo's coffeehouse on South Congress, and he was telling me about his mother when all of sudden he stopped talking and said, "I interrupted myself because if that girl walks by, I'm going to jump up." Then he said, "Don't quote me on that! No more girl stuff." (Earlier this year, an article in Publishers Weekly took the girl-crazy angle.) The woman is young and beautiful, and Gilb has seen her here before. She's achieved that look of studied nonchalance that is hard to pull off well, that custom of Austin's sartorial life in which it is possible to put on whatever may be lying around and convince others that you look like a million bucks. She is an actress, and she is studying a script. She is, of course, also writing a screenplay. We know these things because Gilb went up to her and said, "I want to introduce myself to you because you're so beautiful." Some people say that Gilb is brusque and crude; he is also refreshingly averse to gimmickry. After he introduced himself to her, he told me, "Maybe you should put that in the article."

"Well, you know what?" his friend Rose Reyes, the assistant director of Texas Folklife Resources, says. "It's funny because Dago doesn't see himself that way, that he hits on whoever's pretty. He sees it as pretty girls hit on him. It's true. It's like, What could he do? And I think it's true! I really do think it's true! It's the writer thing ... maybe the fact that his stories tell all these stories about women, and about sex, and about love.

"But I don't want a Dagoberto for a boyfriend or a husband, if you know what I mean," she continues. "He's just not my idea of somebody that I want to get involved with. I just don't think that he's loyal to his partners." Speaking directly to the subject, Gilb says that he is "very happy when I have a girlfriend, and I like it. The only thing that made me unhappy is that when you have a girlfriend you're making somebody else unhappy or your other girlfriend unhappy, you know." Six years ago, Gilb met Maria, a woman -- initially a fan -- with whom he had a child while he was still married to his first wife. (Maria was also married.) "I don't even know what you call what I did," he says. "I went insane. It was just crazy. I went numb. I was getting a Guggenheim, I was trying to write a novel, I was like one of these lucky people they were giving money to, so it was the first time that I didn't have a job and my job was to be a writer and it was like, How do I do this? I totally screwed up. The minute I'm not working, having a confined cage of 40 hours a week, I spend those 40 hours and have a baby. I used to think they were keeping me employed to settle me down. I still get in trouble." Reyes says, "I think Gilb has probably called on his friends more than they've called on him, but I could always go to him with a problem."

Gilb grew up in L.A., pocho -- Americanized. His mother was beautiful; when Gilb was young, she would take him with her when she went modeling at department stores. His mother's friends would tell him that he was a good boy and that he would grow up to be a handsome man. "Even then I knew it was women, their attraction and allure, that I loved," he wrote in an article about his mother published in The New Yorker last year. She was "deceiving and confused," Gilb says, about where she was from -- she claimed Mexico City -- and was always on the lookout for the people who were going to deport her. Her mother was the mistress of a Jewish man who owned an industrial laundry in downtown L.A.; her father was murdered. She grew up next door to the laundry, and met Gilb's father, a German man who spoke Spanish but whom Gilb never lived with. When Gilb was 13, his father gave him a job at the laundry.

Dagoberto Gilb: He didn't like me getting along with workers. I was supposed to have a better attitude, not show them my check, you know, and also he was like protecting me, because he was paying me exactly what they got paid, which was minimum wage. And it was disturbing that they were doing work in adulthood seeing a kid getting paid the same. And now I realize what he was telling me.

Austin Chronicle: What was he telling you?

DG: Well, that you're not supposed to talk with them about your money. I used my money. My mom was kind of a mess and thank God my dad gave me the job. That's how I ate. She would never have fed me. He had the old-fashioned idea where you give your parents your check, you give your mother your check, and I did that for about one week, and I realized, "This is stupid, she just spends it."

It wasn't until Gilb transferred to the University of California at Santa Barbara after three years at a junior college in L.A. that he says he realized what a "pit" he grew up in. "You couldn't believe what a pit it was: perverts, strip joints, car lots." He used to pity people who drove cars that had license plates from Arizona and New Mexico because he thought, "I live in L.A. with all the pretty girls and all the cars." But once he got to Santa Barbara, he "totally wanted to be smart." "I thought that being a professor, just a person that would stand up there and know things, was just ... I thought they were demigods." He became a raving Marxist; radicals at Berkeley were his heroes. He started writing down the words he didn't know. "You should see the book I have, I still kind of hide it," he says. "It didn't do any good, but I did it. Like I'd read Newsweek and every paragraph there'd be at least one word I didn't know."

Still, these were the years when Gilb says he didn't speak. "I remember I had a girlfriend -- I was kind of good at rich girlfriends for a while -- a girlfriend who I lived with, very very rich, very beautiful. She came to Santa Barbara with me. Her parents absolutely despised me, and of course what parents wouldn't die when they see their sweet little daughter run off with me? I mean I look back and oh my God what they must have been afraid of totally makes sense. I couldn't even say 'them' and 'those' right. They'd get mad. I'd say, 'Them guys' and her mom would just get flipped out mad at me and I would get all upset because I'd be at a dinner table and I'd say things wrong."

After he got his degrees (a B.A. in philosophy and an M.A. in religion), he got so tired of late-Sixties, Berkeley-style identity politics that he fled to El Paso. His mom told people that she was from El Paso, and, like the protagonists in his story "The Prettiest Girl in El Paso," he got in a car with a friend and ended up there. "And I just knew it was home," he says. He went to an El Paso newspaper, and talked to someone about possibly being a copy editor, and the nice, patient man listened to everything Gilb had to say and then escorted him down the elevator to the basement so that he could get a job delivering the paper. "But then I'd go to a construction site," he says, "and I'd be able to get a job." His girlfriend, who had come with him from Santa Barbara, got pregnant, and they married. For 16 years Gilb was a carpenter who spent several years in L.A. because he could work for the union there and make much better pay. Off and on he would write.

One day in El Paso, he was part of a construction crew adding on to a museum that is across the street from the English Department at the University of Texas at El Paso. Raymond Carver was teaching there just before his name was in lights, and Gilb was intrigued with someone who was writing stories about working-class people. He took two of his stories over to Carver, who read them and offered to help him get into the writers' workshop at Iowa. That wasn't what Gilb wanted. Why should he be going to school to learn to write? From here, Gilb's writing life is about rejection after rejection. He estimates that his most popular story, "Look on the Bright Side," was turned down 125 times before being published.

The day he got so angry at Texas Monthly, Gilb did in fact go looking for Greg Curtis, but he was out of town. Lou Dubose, who was the editor of the Observer then and is now the Politics editor at the Chronicle, offered to read the article. "I did not think it was great," he recalls more than 10 years later. "This is a contentious friendship. So I wrote him back and said, 'Well, it's not your best work,' something you should never say to an adult. And then I got an angry letter from him saying, 'You know, you shouldn't say shit like that because that's the way your ninth-grade English teacher talks to you and if you think something sucks, tell me it sucks.'" Several years earlier, Dubose had edited an essay about El Paso that Gilb had written, and he hadn't sent Gilb a copy of the edited version before it was published. When Gilb saw what had happened to his essay, he was furious. "We had this epistolary exchange of insults," Dubose remembers, "because although he was right about the way I edited his article, I didn't think the guy needed to attack my mother, you know." Since then, the Observer has instituted the Dagoberto Gilb Rule: Writers get to see a copy of their edited work before it goes to print. Gilb's résumé includes a lengthy list of publications, and this marred essay, the first of his published nonfiction pieces, is duly noted. It says, "'El Paso Perdido' (essay, their title)."

"He's a very pugilistic person," Dubose says. "But I also think he has heightened sensibilities to Latinos being screwed by the establishment, by white men ... and he's going to make sure that he's not ignored, or if he's ignored, someone's going to pay for it. And I don't think that's necessarily unfair. I guess the difficult thing is determining, 'Well, this just is an editorial process that didn't work for me, or this is an editorial process that didn't work for me because I'm Mexican-American.'"

(Recently, Gilb has been in a debacle with Texas Monthly editor Evan Smith over an article that the magazine commissioned from him. They wanted 3,500 words. He turned in 7,700. The article is a literary essay titled "A Pocho's Tour of Mexico" that Texas Monthly wanted to shorten and restructure. Smith advanced Gilb $2,000 for his travel expenses. Harper's is going to publish the article in its entirety.)

Seven years after his earlier frustrations with Texas Monthly (the article about gangs in El Paso was never published), Gilb was offered a job teaching creative writing at Southwest Texas State ("one day, when I felt like I was in a little trouble, I decided to take a job teaching English," begins one of his essays for the Observer). He had already published three books: two collections of short stories and a novel, The Last Known Residence of Mickey Acuña. Books about drifters, mechanics, carpenters, men wanting women, and people who don't talk different just because they're characters speaking in a work of literature. He had received a creative writing fellowship from the National Endowment for the Arts, a Whiting Writers' Award, a Guggenheim Fellowship, the Ernest Hemingway Foundation Award, and was a PEN/Faulkner Award finalist for The Magic of Blood, a book of short stories. In 1993, the Texas Institute of Letters (TIL) decided that he had written the best short story in Texas that year and the best book of fiction.

One month into his first semester teaching at SWT, The New Yorker published "María de Covina," which is included in Woodcuts of Women (see review at austinchronicle.com/issues/dispatch/2001-01-26/books_feature2.html). He was also conducting a writing workshop that didn't have any Chicanos in it, and he knew that the two people he wanted to join the workshop -- both Chicano but not registered students at SWT -- would have something to contribute to the class. His classroom is his kingdom, he felt; he should get to choose who could and could not sit in on his class. The SWT administration argued that a lot of time had been spent deciding who got to enter the program, that teachers didn't get to just decide willy-nilly who was going to be in the program. Gilb's solution? Have a writers' workshop in your own apartment, every Friday night, and call it -- only somewhat jokingly -- the "Undocumented Illegal" writing workshop with five Chicanos who were interested in writing.

Oscar Cásares, who is now working on a collection of short stories at the University of Iowa Writers' Workshop, was one of the students. He met Gilb at a party for Rolando Hinojosa-Smith, a writer who teaches at the University of Texas. "And a few months had passed," Oscar says, "and I wrote him a letter and said, 'I don't know if you remember me but we had a beer or two at this party, and I know you're teaching this class and I'd really like to get in on it, and I realize you can't just let me in the class but I'd be willing to send you some work and let you look at it.' And he called me the morning he got the letter and he said, 'I'm going to let you in on the class not based on your work but based on the fact that we did have a couple of beers together.' And as it turned out, I couldn't get in the class because of whatever powers that be there were, they just kind of frowned upon somebody coming in off the street." (Later, Oscar was allowed, and, in fact, encouraged to audit several classes in the creative writing program, based on a submission of his creative work. Tom Grimes, who directs the creative writing program, wrote a letter of recommendation for him when he applied to enter the Iowa Writers' Workshop. Two of the five students eventually entered the M.F.A. program. When Gilb offered this workshop, none of the students had applied to the program.)

"Okay, let's take this other instance at Arizona," Gilb says. "They're looking at three people for a position for a Latino writer at the University of Arizona. Now what does Latino mean in the Southwest? Okay, I just assume that that means Mexican-Americans. I mean, what would you be wanting at an all-Anglo faculty? But no! They were interviewing besides me a Cuban and a Puerto Rican, which in the East would be interesting because they all live there but in Tucson, Arizona, there is no Cuban community, there is no Puerto Rican community, and it's just, like, appalling that you would suddenly call that Latino. Cubans are white people, I'm sorry. They're not Mexicans. They're not interested in Mexican-Americans. But to bring them to a university in the Southwest and to say that you're doing Latino stuff now is like, well, that is just ridiculous. This is Chicano land and you don't get to just pretend that we don't exist here."

He took the job.

"I was teaching very rich kids, and I really felt like a monkey. I felt like I'm getting paid nothing, there's these rich kids -- nice, too, all nice people, I don't dislike anybody. But there's this part of me thinking, 'This is so unfair, this is so weird that I'm helping rich people get more, like, exotic' and giving them more information for their material whereas my own region's kids don't get this in their schools. And I happened to be living in a poor neighborhood in Tucson, poor Chicano neighborhood, and there was a library and there was a literary Chicano group meeting, and at that time I said, 'If I ever do this again, I'm going to go into the community, and as I'm getting paid well at a school teaching the rich white kids, I'm going to go into the community and do the exact same thing."

Gilb was asked to be a member of the Texas Institute of Letters in 1991; from 1994 until 1997 he was a councilor of the organization. That's when he made certain that the scholar and writer Américo Paredes, who died in 1999, received a lifetime achievement award, and, after that, that Rolando Hinojosa-Smith did as well. "And I really thought they were going to fight me," he says. "And I had it in my mind that I was going to make a total scene and quit right there: 'I quit and I'm going to write an essay about it.' I'm sorry, but these people are as important to our community as your people are to your community but in the outside world I don't particularly rank your people very high, either, but I try to be polite, so be polite to me."

No one balked at those suggestions, but when Gilb wanted David Montejano, the former director of UT's Center for Mexican-American Studies and the author of, among other titles, Anglos and Mexicans in the Making of Texas, 1836-1986, to become a member, he says he had a "little battle" getting him admitted. It is possible to receive major awards from the Texas Institute of Letters for, say, best work of fiction but not actually be asked to become a member. "He won the big prize one year," Gilb says, "and then they wouldn't let him in. [TIL] let all these dorks in and somehow [they] say, 'Oh, I didn't like that sentence'? 'That sentence wasn't good enough'?" Gilb told them, "'The book is taught in so many courses! Shut up!'" "And I think they liked me for that," he says.

Gilb is on a mission that people do not always understand. Sometimes that is not their fault. There are people who say that he complains a lot for someone who gets published in The New Yorker (and, soon, Harper's), has a teaching job that allows him time for writing, and has racked up writing award after writing award ("I can bitch like anybody," Gilb says, "although ... if you look at the history of my complaining, you'd find out that I wasn't so wrong"). There are critics who find it difficult to ascertain whether, as Gilb seems to be indicating, the establishment is out to keep him (and other Mexican-Americans) down -- or just Gilb's ego. Does it happen to Gilb because he is a) a blue-collar Chicano who doesn't talk pretty but has been quite successful, or b) because he can be loud and irritating while wearing a chip on his shoulder?

"I think that's bullshit," Reyes says. "I think it's real easy to say, 'Oh, this is all about Dago and his ego' but ... I think that it takes people like Dago that don't give a shit. And yeah, sometimes they'll look out for their own personal gain but he'd be the first one to stand up for one of his colleagues or when he just thought that somebody was being racist or whatever the case may be."

To complicate things: Gilb absolutely does not want to be a role model of Chicano activism. "Some part of me wishes that I just would back off," he says, "because it pisses me off that I have to do this, but I'm just like, 'You can't do this,' and I don't really feel like it's up to me even. I don't even know that it's [directed] at me, that it's not even just me. There's not enough of us." But he also says, "I've always gone, 'I'm not a Chicano, I'm just a culture of me, one guy.' This is it. Fuck you, I don't need to be your Chicano-whatever. And I'd always kind of fight it off that way. Because I don't want to be the representative." He claims the long-held right of the artist to be left alone. And who can blame him? Now that he's made it (though he says there are two books he absolutely must write "before I go to heaven"), and had to work so hard to make himself heard, being left alone may be his biggest challenge of all. ![]()