Faith Healers

A Day in the Life of a Christian Treatment Center

By Emily Pyle, Fri., Dec. 15, 2000

Fort Worth is not built perfectly flat, but it looks that way, as open to the sky as if it were set on the edge of a marsh. Standing in the shadow of downtown's two tallest buildings, you can see the red-brick ruins of the Swift Company packing house that built the city, back when it was Cowtown, when cowboys drove herds of cattle down Exchange Street and the trains ran day and night carrying sides of beef up to Chicago.

Not far from the city center is the part of town locals call Rock Island, where Fort Worth's wealthy once built Gothic houses at the top of long lawns that slope down to Samuels Avenue. Later, small bungalows and cottages were built on the other side of the street, and they changed hands too many times and fell until disrepair. Today, Rock Island is the kind of older, boarded-up neighborhood that figures in the ghost stories every town tells about itself.

At 747 Samuels Avenue sits one of the neighborhood's newer buildings, rebuilt from the ground up 10 years ago. Unmarked, and set apart from the other houses by its size and a small parking lot hidden behind a few trees, the two-story, wood-shingle building is home to some 20 women and the staff that looks after them. If all goes as planned, each of the women will spend eight months in Teen Challenge's Fort Worth home. They may come from Texas or Louisiana, from Oklahoma or New Mexico or New York or as far away as they need to come; there are more than 120 Teen Challenge centers in the United States alone, and the waiting lists at many centers are still months long. Few of the women are "teens." Most are in their 20s and 30s, though the oldest is in her early 40s and the youngest 19. Some come on the advice of friends or pastors, some are probated or paroled here. They are mostly middle-class, mostly with some religious background, all former alcoholics, heroin or cocaine addicts, or victims of -- in the Christian-therapeutic jargon that is commonplace at the center -- "life-controlling" problems.

Fort Worth Teen Challenge Director Larry Adley and I sit in his office while he explains the center's philosophy, though it sounds less like an explanation than like a sermon. Anyone who has been to a revival is familiar with the style -- the speaker's progress from point to point and regular return to one oft-repeated phrase. It is impossible to take notes or ask questions, and after a while I give up and let my notebook lie in my lap.

What I get from the sermon is that "drug addiction" -- as Adley repeats many times -- is not the problem. The problem is an underlying suffering, memories or feelings so painful that they drive individuals to heroin, to crystal meth, to promiscuity, to whatever numbs or distracts or provides temporary relief. Until the underlying wounds are healed, Adley says, there is no cure. This is hardly a revelation to drug counselors in any program; it is the next point he brings out, plays on, elaborates, that is different. The cure Adley suggests isn't Valium or years of psychotherapy. It's Jesus. Another thing Adley says -- and it will be repeated to me time and again by various people before I leave -- is this: "Structure is like a cast: It won't heal you, but it will keep everything in one place until it comes together."

The voice of Mary, the night supervisor, wakes the women of Fort Worth Teen Challenge at 7am exactly. For the next 45 minutes they shower in assigned 15-minute slots and clean their rooms to the center's exacting standards (nothing on the beds, nothing on the floors, clothes in the closet with -- one woman tells me -- all the buttons facing the same way). Breakfast is at 8:30, then chores for the first of three times that day, and afterward "Praise & Worship" at 10am. The women have Bible-based instruction twice a day: group classes at 10:30 and individual study in the afternoon.

The program is a year long -- eight months at the main house, then four more at the "Re-entry Home" down the street, where women are allowed to take outside jobs or attend school. For the duration of the program, the women have no contact with anyone from the outside except for immediate family, and for the first two weeks they have no contact with anyone outside at all. After two weeks they are allowed three 15-minute phone calls a week. (Beth, who has been here nearly a month, tells me how she divides her time: five minutes on the phone with each of her two young sons, two minutes each with her mother and sister.) For four months, the women do not leave the grounds of the house and have no visitors. In the fifth month, the center gives them weekend passes once a month to visit family; after six months they get passes every Saturday.

The regimen is strict, but the staff of teachers, counselors, and supervisors tries to soften the institutional feel of the place. Women are permitted to bring personal effects with them from home, within limits. Bibles are okay, old journals and diaries are not -- nothing that will help them hang onto a past that, as far as Teen Challenge is concerned, is over. Back rubs and bare feet are forbidden, along with almost any medication, anything but aspirin and vitamins. Women on psychoactive medications give them up before they come to Teen Challenge, along with drugs, alcohol, and cigarettes. One girl had two molars pulled here with "nothing but ibuprofen." ("God got me through it," she says.)

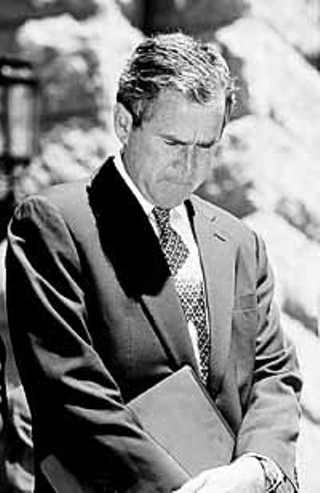

Faith-based programs like Teen Challenge aren't new, of course; churches were once a primary provider of social services (which were called charities). But as the federal and state government began to bear more of the social service burden, churches did less. For a decade now, conservative politicians have been making the argument that faith-based programs can provide something government programs do not. (Gov. George Bush's Christian conservative guru, Marvin Olasky, even suggests that these programs provide a spiritual benefit for both the recipient and the giver of the charity.) And it is evident that in an age of budget reduction and diminishing government social services, politicians are eager to see religious organizations pick up the people government programs have turned out onto the streets. These new programs -- offering job training, child care, soup kitchens, or treatment for substance abusers -- are the centerpiece of the "compassionate conservatism" espoused by our presumptive president-elect George W. Bush.

At Gov. Bush's urging, Texas was the first state to jump on the "charitable choice" bandwagon, made possible by Section 104 of the Personal Responsibility and Right to Work Act passed under President Clinton in 1996. Section 104, the charitable choice provision, prohibits states that fund private programs that provide social services from discriminating between religious and secular service providers. Nor can the state require faith-based programs to downplay their religious message in order to receive funding. States can no longer, for example, require the removal of religious symbols from buildings where social services are provided, or insist that prayer be discontinued. Section 104 does require states to provide nonreligious programs of equal quality, and prohibits religious programs funded by the state from turning anyone away because of reasons of faith. At Bush's urging, the Texas Legislature took support for faith-based programs a step or two further. House Bills 2481 and 2482, passed in 1987, exempt nonmedical faith-based programs from state licensure and inspection requirements, and allow faith-based child care and child-placement services to be accredited by private, faith-based entities rather than by the state.

Loosely affiliated with the Assemblies of God Church, Teen Challenge operates on the uncomplicated premise that the cure for addiction is to build a personal relationship with Jesus: to live by the principles laid out in the Bible and to experience rebirth through salvation. Toward this end, lessons are held twice a day -- group Bible study in the mornings and individual study of Bible-based curriculum in the afternoon. The individual study exercises have titles like "Now That I'm a Christian" and consist of Bible verses to memorize, with corresponding readings and worksheets with cartoon illustrations. The same exercises, though not necessarily in the same order, are assigned to each woman individually by the classroom director, a Bible-college graduate named Charlene.

On this particular Tuesday, though, we skip morning classes to go to a meeting of the Women's Ministries at a nearby church. The women of Teen Challenge are often invited to churches to sing and testify, but today we sit in the audience and listen to Tim Grant, director of Pleasant Hills Children's Home. Grant is a gray-suited man with a moustache and manic energy. He bounces on the soles of his feet as he describes the miracles at the Children's Home. They've involved children who have been neglected and abused, the offspring of drug addicts and drifters. "Satan has literally stolen the first eight or 10 years of these children's lives," Grant whispers. He throws his head back, grins, hollers. "But they are bought back! Praise the Lord! Now, you could take them and put them in another home and they would feed them and put clothes on their backs, and maybe better clothes than we can -- but they would not give them the power of Jesus and that is the only thing that can save them!" One of the Teen Challenge women wraps her arms around herself in the pew and rocks forward and back; her own young son is with her mother, I know, several thousand miles away. While Grant talks, the husbands of the women in the Ministry load box after box of canned food into a van outside until it is full. The women are generous supporters of both Teen Challenge and Pleasant Hills.

As Grant finishes and the congregation leaves the church, an elderly woman in a red wool suit bends over our pew. "We're so glad to have you all here," she says brightly, encouragingly. "And we've brought just bags of gorgeous clothes for you, so you can dig through and take whatever you like." She smiles generously. "We've got a whole bunch of very beautiful hats for you -- brand-new hats! Do you like hats?"

Clothes are the least of the donations to Teen Challenge -- everything in the main house and the smaller re-entry home is a gift from somewhere. Sherma, the induction director, leads me around the house one afternoon and points out the donations: the cushions on the sofa, the tiles on the kitchen floor and the sheets on the beds, not to mention all the food; she throws open a cabinet door in the storage room so I can see row after row of restaurant-sized cans of vegetables.

The donations are all Larry Adley's doing, Sherma says, the direct result of his 25 years building the reputation of Teen Challenge among supporters in the community. In 1975 Adley took over the center when it offered little more than afternoon programs for local children. There was just the drafty old house with its two working bathrooms and nothing but rice and beans to eat. Sherma tells me a story from the early days: The women and staff members sat down to eat and one of the staff members, a Teen Challenge graduate, was asked to pray. She stood and said "God, we need meat. You need to send us some meat, God -- and not hot dogs, Lord! Real meat!"

"And I was here and saw this with my own eyes," Sherma says. "Two men drove up in a black pickup and said 'Do you all want some meat?' and just started unloading it from the back." To ask where the meat came from is to miss the point of the story -- God provided. It is the kind of story Teen Challenge enjoys.

With its needs met by charity, Teen Challenge has little reason to take advantage of the Charitable Choice provisions provided by federal law, and thus far has avoided government funding. "Where the government funds 50% of the program, they are going to want to control 50% of the programming," Adley says, and that's the end of the conversation. In fact, it seems as if no one here is aware that this very sort of program has been at the center of debate in the presidential campaign. "I'm not too interested in politics," one staff member tells me. "My focus is more on the Lord."

Bush's Faith-Based Guru

Yet politics and policy have made a difference. There is no denying that Teen Challenge has benefited from the state's loosening its hold on faith-based programs. In fact, Teen Challenge itself has been at the heart of the struggle. In 1995, the Texas Commission on Alcohol and Drug Abuse (TCADA) threatened to shut down a Teen Challenge home for men in San Antonio, citing a list of violations, chiefly the program's failure to employ drug counselors licensed by the state board. At the time, UT journalism professor and fundamentalist Christian publisher Marvin Olasky stepped into the fray. By rallying some 300 Teen Challenge supporters gathered at the Alamo in June of 1995, Olasky placed Teen Challenge's fight with TCADA on the pages of The Wall Street Journal and himself into Bush's line of sight.

Bush also sided with Teen Challenge, and in December of that year, TCADA gave in to the political pressure and granted Teen Challenge an exception from the state regulation. The commission's only action was to rule that Teen Challenge couldn't be registered as a "licensed drug treatment program" -- a slap on the wrist that was barely noticed. "Now they won't come back and bug us any more," Teen Challenge Executive Director Jim Heurich told reporters at the time.

Meanwhile, Bush sought out Olasky, who had been a regular on talk shows and behind the scenes in Washington in the early Nineties, when his book The Tragedy of American Compassion was required reading for Congressional Republicans dismantling federal welfare programs. (Olasky has since expressed dissatisfaction with the way his ideas were used, comparing legislation the Newt Gingrich-led House passed to helping a stabbing victim by pulling the knife out of his back.) Under Olasky's guidance, Bush convened a 16-person Governor's Advisory Task Force on Faith-Based Community Service Groups. The task force's 1996 report to the governor, "Faith In Action: A New Vision for Church-State Cooperation in Texas," is slick, compelling, and packed with quotes from Martin Luther King Jr., Thurgood Marshall, and Anne Frank. The report is mostly made up of success stories (and anti-success stories, like the account of how Joy of Jesus, a successful job-training program in Detroit, was undone by government intervention in the form of funding). From these stories, the report draws conclusions and makes recommendations that have become the bedrock of Bush's approach to faith-based aid. The 1977 laws Bush supported -- which allow for the deregulation of licensing and accrediting -- are lifted directly from this report, which advises the state to "allow for an alternative oversight mechanism for faith-based providers who ... believe a non-governmental entity can better credential and accommodate their program."

The new laws make it easier for someone like Jamie -- a former accountant who, though unlicensed, provides what Fort Worth Teen Challenge calls counseling. She also supervises the re-entry home. "I wouldn't call myself a counselor because I haven't had the training and the licensing," she says, cautiously (though that's how Adley introduces her to me). "When God puts something in my heart to say to someone, I just say it." The women talk about Jamie with awe and affection and quote to me things she has told them.

Jamie and the brand of counseling she delivers ("I yell at people so I won't have to listen to them," Jamie says) are probably the least of the state's worries with places such as Teen Challenge. In 1998, according to the Houston Chronicle, a suit was filed against the Assemblies of God Church and the Dallas Teen Challenge Boys Ranch in Winnsboro, alleging that a plaintiff identified in the suit by initials only was sexually abused by a staff member in 1996. The staff member, Curtis James, was enrolled in the Life Challenge program -- a program for adults with drug abuse problems. As part of his program, he was working at the Teen Challenge Ranch, although his criminal background precluded him from working there legally. An investigation by the Texas Dept. of Protective and Regulatory Services turned up mixed results -- the department found "sufficient evidence" that abuse might have taken place, but could not conclude by a "preponderance of evidence" that it had. And the lawsuit filed against James was dismissed by the court in Tarrant County.

The Jesus Factor

It seems unthinkable that anything improper could happen here in Fort Worth, where Linda, Beth, and I sit on the porch in the late-afternoon sun. We talk about the garden, which won a state award this year, about the places we come from and what trees and vegetables will and will not grow there. The dog, Gracie, chases something invisible across the grass, and Marie plays basketball by herself in the driveway. And the talk drifts slowly, though not as slowly as I expect, to why they are here. "I never was into the drug life till I was 30 years old," Linda tells me. "I was raised in a family -- you know, raised very sheltered. It wasn't until after my divorce that ... I was just really naïve. I guess that's sad, but I was."

There are others who started drugs at 13 and 14, who bought armfuls of Sudafed at the drugstore at midnight to make crystal meth, who lived on the streets, stole, got caught, went to prison. They tell me about that and also about abuse, anger and grief, the death of parents and friends and children. I'm surprised how readily the stories are volunteered to me, how quickly -- the abortions and prison sentences and terms in mental institutions -- until I realize that these are women whose private lives have been taken away. These are stories that have already been told to angry families, to social workers, psychologists, and judges. They have not stopped telling them even here, though Teen Challenge encourages them to talk less about the past and more about redemption and what Jesus has done for them. These tales of redemption are told a few times a week, when the women from Teen Challenge visit local churches to sing and give testimonies. People who make contributions, after all, want to see results, salvations, returns on their investment.

We watch a van pulled up in the driveway 20 yards away, a new girl and her family unloading what they have packed for her stay. It is hard to see her face, but not hard to read the tense set of her shoulders. She does not look much at us, sitting on the porch, and we are quiet. "I remember my first day," one woman says softly, suddenly. "I remember smoking my last cigarette there in the driveway. My hands were shaking -- the hardest thing I ever did, coming here."

There is an odd ambiguity about the ages of the women here. Carrying pink, three-ring binders and sitting over worksheets with cartoon illustrations, they look younger than they are, or older. Some you would swear are not out of high school are 26 or 27. Some who are older look like children, as their lips move while they memorize Bible verses. And some of the youngest are the most secretive and bitter.

Lily has had a bad day. As part of her exercise, someone has written an evaluation of her progress here, and the evaluation is too good, she says.

"Maybe you're changing and you don't know it," somebody suggests.

"I know, but -- I don't want to," Lily replies.

"It isn't what you want. It's what God wants," adds another woman.

Lily frowns at the page. She finished two years of college and was good in school, she says. "But," she begins -- then she shrugs. She is 22 and was paroled here. She has "a lot of bad defense mechanisms" and has been in eight other rehab programs, all of them secular except this one. Someone asks her if Teen Challenge is different. "I would say it's very different," she says, watching the opposite wall. I don't ask anything more and neither does anyone else. Instead, a woman reaches over and pulls softly at Lily's short hair. "You know how I can see you? With your hair all gelled up and sticking out like this."

"I used to have dreads," Lily says, and smiles, suddenly. "Rainbow dreads."

Many of the women here are small-town women. They talk and smile like small-town women, and like small-town women they do their hair and their make-up very carefully and very well. With some exceptions, they are not wealthy or from wealthy families (although one women is partner with her mother in a successful day care business). Income doesn't matter, though, because Fort Worth Teen Challenge is free. Women are accepted first-come, first-served. All they need to pass is a physical exam and a phone interview with Sherma. And all Sherma wants to know is that applicants want to change, and that they are coming voluntarily, not pressured by families or coerced by courts. "It's hard to tell sometimes," Sherma says. "Because sometimes people will say the right things just to stay out of prison." Even when courts aren't involved, she concedes, it is hard to tell who is sincere, whom the program will work for and who it won't. "We aren't for everybody," she admits. "Sometimes a person just isn't ready yet. Maybe later they'll be ready."

There is no reliable predictor, she says, that tells her who is ready and who isn't. No pattern that predicts who stays and who goes -- not age, not the extent of the addiction, not previous religious background. The only factor the success stories have in common is what Sherma calls "the Jesus factor." "Ultimately it's who really opens their hearts to Jesus. That's the only difference. That's what makes the change."

Proof in the Statistics?

It either makes sense to you or it doesn't. If you can make the mental leap and find the connection between Jesus Christ and the veins in a young girl's arm, then that's the end of the story. If you can't, then the story never ends. You trail off demanding facts, statistics, answers -- proof. You look for numbers and you find there are none. Because none exist. The Texas Commission on Drug and Alcohol Abuse doesn't keep track of faith-based programs because, under the new laws, programs that exempt themselves from state oversight aren't required to provide the state agency with statistics on success and relapse. And the faith-based programs that remain under state oversight are not listed separately from secular programs, so their statistics are included with the others.

It is also evident that the programs -- at least Fort Worth Teen Challenge -- do not keep very exact figures. Larry Adley cannot tell me offhand, even the rate at which women complete the program -- successfully or not. One study, conducted in 1975 by Dr. Catherine Hess, medical director of New York's first methadone program for drug addicts, suggested that Teen Challenge had a success rate of 86% -- three or four times current estimates of the success rate in secular programs. It is a figure often cited by supporters of the program, but Bill McColl, executive director of the National Association of Alcoholism and Drug Abuse Counselors, dismisses both the statistic and the study. Hess's study was done too long ago, McColl says, and conducted with an "extraordinarily small sample group." (Hess studied only the members of the 1968 class of one Teen Challenge Center in New York.) So it has almost no statistical validity.

"In my opinion, there is no research at all," McColl says. "People will tell you 'We have all this data,' but when you come to look at it they're using small sample groups, or anecdotal evidence, or there's no control group." McColl and most traditional treatment-providers are reluctant to say faith-based programs don't work, but the trend towards deregulation, especially of practicing counselors, makes them nervous.

"Maybe if it does get researched, we'll find it's head and shoulders above everything else," McColl says. "But personally, I believe that a science-based approach will yield the best results. There is an established body of knowledge on how to deal with people with alcohol and drug addiction ... Flat out, this is a disease, a chronically occurring disorder like asthma or diabetes, and it has [treatment] success rates similar to other chronic diseases," McColl says. "Relapse is part of this disease. When you're asking people to change behaviors, you have a lot of relapse."

Of course, that drug addiction is not a disease -- that a permanent cure is once and for all possible -- is exactly the point Teen Challenge and many faith-based programs like it are trying to make. "If I didn't believe in healing, I believe I'd get out of the Christianity business," Adley says. "What would I be in this for? There has to be a point where you stop defining yourself by what you used to be."

Complete healing and what Adley calls "catharsis, the turning point," stand in stark contrast to the one-day-at-a-time approach of many secular programs, and may well be faith-based treatment's biggest selling point to the government and the public. "The typical alcoholic treatment says you're always an alcoholic," says Stanley Carlson-Thies, director of social policy studies at the Center for Public Justice, a Christian, public-policy think-tank. "You'll always be an alcoholic, so stay away from alcohol, stay away from people drinking alcohol, at parties you'd better stay away from the bar. A program like Teen Challenge, what they do is they take someone whose life has been trapped by drugs, get them off drugs, and they can put them back on the streets into essentially the same situation and they don't get trapped."

Faith-based programs have their own share of relapse, of course. There are women here at Teen Challenge who have been through the program two or three times before, who have left the rarified atmosphere at Samuels Avenue and found the world as hard to navigate as it was before. So the question isn't really whether faith-based programs do or do not work. The question is whether they are ready -- without study, without solid scientific backing, with no proven mechanism in place to prevent their abuses -- to be promoted and funded by state and federal government.

At a press conference in July 1999, Bush pledged that, if elected president, he will dedicate roughly $18 billion in his first year in office to tax incentives for "charities and other private institutions that save and change lives." He has also said he would create an "Office of Faith-Based Action," but the main thrust of his proposal was to encourage the public, via tax breaks, to give more to charity. Whatever Bush does in office, his presidential campaign has brought faith-based programs to the table and, as Carlson-Thies says, "We are going to see them on the table more and more."

Before I leave Teen Challenge in Fort Worth, I'm given a book of stories. The book was printed for Fort Worth Teen Challenge's banquet and fundraiser two weeks earlier. It is called the Book of Hope and it is something like a high school yearbook: each woman's picture lain out on a page with her story next to it. I flip through and find the women I know -- Heather, JoMarie, Lisa. And then there are a few faces that are already missing, women who were here a few weeks ago and aren't here now. Different faces, yet the stories printed in the small book are all so similar.

Elizabeth, who said she would "stay the entire year" and "walk out a new woman in Christ," is gone, and they give me her empty bed to sleep in while I stay. After the lights are out at 10pm, Elizabeth's old roommate lies awake and tells me how she drove a car through the wall of a friend's house into her living room while drunk. She tells me that she must have worked for "every single 7-Eleven" in her hometown, and about her days spent riding and drinking with Hells Angels. ("They never knew I was part Mexican, that I could speak Spanish.") She talks in veiled terms about her childhood abuse, her anger, and her 13-year bout with drug addiction. She tells me how missionaries miraculously handed her a flier for Teen Challenge while she was standing on her drug dealer's front lawn.

"I always knew it would take a place like this to save me," she says. While she talks, outside in the dark the trains run by one after another all night long. ![]()

Got something to say on the subject? Send a letter to the editor.