Saving All Our Changes

Goodwill Computer Museum Curates Cyber-Castoffs

By Michael King, Fri., Dec. 8, 2000

Try to remember when "computers" first became an ubiquitous part of your daily life. If you're under 30, you might well be thinking "it seems like forever." But if you're over 30, or even pushing into your dread late 40s, you might recall a time when "IBM-PCs" were unwieldy beige behemoths implacably and somewhat mysteriously conquering the desktops, secretary by secretary, at your office. Then the secretaries began to disappear, but the machines stayed.

Maybe one of your richer, nerdier friends had a PC clone at home, upon which he laboriously wrote reports and reviewed spreadsheets, brought home from the office on 51é4 inch floppy (really floppy) disks. "Video games" were still a largely novelty item in barrooms, tucked beside the pinball machine -- for a quarter you and a friend could "ping" an imaginary, monochrome "pong" until the beer kicked in, and beyond. Finally came Windows, and then Solitaire.

It may seem a considerable time and distance until the current moment of technological paradise: when even your virtual great-grandmother has several gigs of ever-virginal memory glowing in her indigo laptop, every kid on the block is disemboweling zombies on warp-speed portable PlayStations, and you and apparently everyone you know is hard-wired into something the slick-mag salesmen call the "virtual community" (emphasis, harsh, on the adjective).

Lost your cyber-innocence and don't know where to find it? Consider a visit to the Goodwill Computer Works, where they have just the time machine you will require. Behind this unobtrusive strip-mall façade (smartly distinguished by a neon-tailed mouse), and the unimposing, no-nonsense used-computer store within, hides a Magic Doorway into Another World. Walk straight through the retail store into what at first appears to be an ordinary workroom/storage area -- and as boldly as Mario and Luigi in search of Princess Toadstool, enter cyber-history.

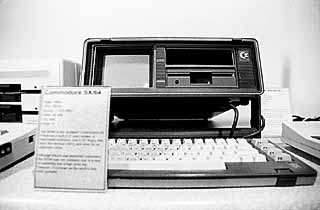

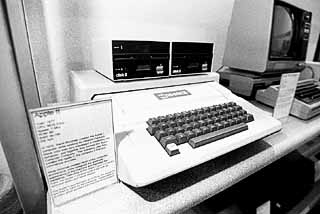

The Goodwill Computer Museum -- quaintly titled "Relics of the Past" -- is a fascinating and affectionate attempt to build a permanent collection of mini-computers and computer-game consoles, most of which would be otherwise dead, gone, and almost certainly forgotten. Here is where Amigas, Ataris, Apples, Commodores, Kaypros -- and their many lesser-known brothers and sisters -- go to quiet glory. Should you still long for a glimpse of that original gray box of a Nintendo on which you first learned to play Super Mario Bros. (only to abandon it one day for a faster, sleeker, but hardly more loyal PlayStation) -- well, here she is. And even if you think you don't give a damn about computers or video games -- and certainly not obsolete or "antique" machines -- a few minutes among these now lonesome tools and toys might give you a moment's pause. In the air there's an undeniable (if mechanical) whiff of Gepetto's Workshop, or at least, of Toy Story 3.

As you might guess, the collection began more or less by accident, in the working rhythm of a Goodwill retail facility whose primary purpose is to sell secondhand computers and related hardware/software in order to raise money for training and employment programs. (Indeed, the retail operation is itself a spinoff of some of Goodwill's job training programs, those devoted to computer technology.) That aspect of the operation is a classic Goodwill business: fully operational computers and printers, some less certainly so, shelves burdened with miscellaneous accessories of every imaginable kind, buckets of hard drives so cheap that if they don't work as intended they can have a second life as perfectly serviceable paperweights ... and so on. Goodwill's director of marketing, Debra Danziger, says the retail operation is the symbiotic result of the organization's work adjustment and training programs, which are provided for people experiencing any of a number of "barriers to employment." That can include physical or mental disabilities, but also encompasses "homelessness, illiteracy, or youth in at-risk situations." Donated computers were at first directly used in training, but soon became such a flood that the recycling program came of age. Since the obsolete PC statistics are themselves sobering -- some 55 million nationwide, bristling with heavy metals and other toxic components, are expected to head for landfills in the next five years -- the recycling operation is itself a public service. "We've recycled roughly 60,000 computers in the past two years," says Danziger. "We try to use everything we get."

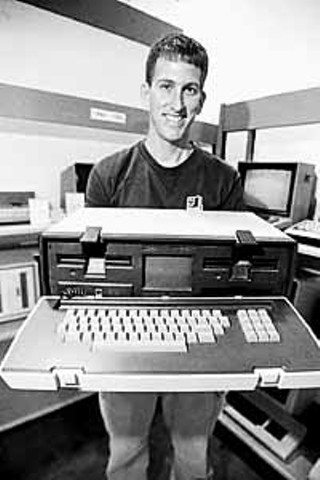

Goodwill workers at the original downtown location on Baylor set up a single shelf to display those donated computers so "old" (in computerese, an extremely relative term) they couldn't be refurbished and resold. When the facility moved to its current, larger quarters on Research, the collection began to grow in size and interest. It soon became the pet project of hardware technician Alex Bilstein, a young UT art history grad who first came into the store as a shopper, then a volunteer, then discovered he had a job. "Computer history has always fascinated me," Bilstein says. "When I first came into the store, there was really nobody taking care of the old computers like this. A lot of them were just being trashed. The idea was, 'This is really old, nobody wants this.'" Bilstein readily persuaded his new boss, manager Jamey White, that the older machines had an intrinsic historical interest beyond their direct-sale value. With White's encouragement, Bilstein (who has since moved elsewhere to work as a Web designer, but continues to volunteer his time to work on the collection) began saving the old machines. "At first, when the collection was still small," Bilstein says, "customers would occasionally ask for a price on one of the old machines."

Once the space was dedicated and Bilstein had established the museum-style displays (complete with his attentively explanatory labels), computer aficionados began donating machines specifically to the collection: "Customers wanted to find a home for their old machines." In addition to outright donations, several local computer collectors have helped Bilstein with research, as he tries to establish the provenance and history of the museum's more obscure acquisitions. "When I started," Bilstein says, "I knew more about old video game systems. But customers have helped me with particular computers, and when something unusual comes in, I'll do research on it." One thing he discovered quickly is that there are very few other museums in the country devoted to maintaining, displaying, and chronicling vintage computers. "There are several virtual museums on the Web," says Bilstein, "and the Smithsonian has a National Museum of American History that contains a computer history collection. But except for one or two places on the coasts -- and another in Bozeman, Montana, of all places -- there are no actual museums devoted to this technology. There are some private collections," he adds. "Probably some collectors in Austin have as much as we do, but it's all in storage."

Austin programmer George Currie, who says he still has the Commodore VIC-20 ("with a whopping 3.5K of RAM and a cassette drive!") he got in 1982 when he was 17 years old, applauds the work Bilstein is doing with the collection. Currie believes saving the machines themselves are also a way of "saving the stories about the device that's changed the world as we know it.

"One thing that many people don't see," he says, "is that the type of person who would think to create a museum is the type of person who thinks it important to make an effort to save these machines. It's refreshing to talk to someone who mourns the loss of some interesting piece of computing history. Alex goes through great efforts to make sure that these machines are not simply chucked." Wireless software developer Ben Combee, who has also helped Bilstein's efforts, adds, "It's one of the few installations in the country with such a full collection of computers from the 1970s and 1980s."

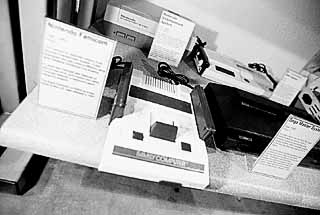

Welcoming visitors, Alex Bilstein readily shares his fascination with the machines he and his colleagues at Goodwill have collected. "Each one of these has a story," he says, gesturing among the shelves. Sometimes it's a marketing meteorite: "This one was called a 'CroMemCo,' after Crothers Memorial Hall at Stanford," he says, "where its student designers attended school. It did well initially, but it disappeared really quick when the IBM-PC took over." ("CroMemCo reached its peak in 1983," reads the display label, "with ~500 employees and $55 million per year in revenue. They were also the preferred supplier of microcomputers to the People's Republic of China.") Other, less obscure machines have an honored place for somewhat less scholarly reasons, Bilstein says. "This one's a Commodore 64. It's not rare, but it was immensely popular. People have a lot of affection for them, and we still fire it up just to show off." Here is also the good gray Nintendo, as well as its lesser-known Japanese equivalent, the Famicom (for "Family Computer"). The Famicom -- which looks like a Samurai version or something Bender might use on Futurama -- played the identical games as the good gray box.

One of the prize exhibit pieces ("This is our biggest draw," says Bilstein) is a mysterious, partially denuded metallic cubical donated by a local salvage company, labeled the "Cray EL-94." "That's the one that most people tend to stop at," says Bilstein, "especially people who are really into computers, the more powerful computers. You don't often get to see a Cray: a supercomputer that was used by the government and really large corporations and institutions. This was one of their small, 'affordable' models: it cost $100,000, plus a $1,000 per month maintenance contract. The Cray was superpowerful for certain tasks -- it was meant to do one task, so it does it very, very well. ..." Goodwill's Cray EL-94 is still a shadow of its former self. "We don't have an operating system or drives," said Bilstein, and the Cray's label invites customers to provide any additional parts, programs, or information they may have. Says George Currie: "To have a Cray anything is just really cool."

Nor is the Cray the museum's only mystery. "There's a couple we don't know anything about. Here's something called an IBEX: with 8" disc drives, very unusual looking. Nobody has heard of it, or knows what it is. And here's a Zilog Z-80. The Zilog company made chips, but they weren't known to manufacture computers. ... It may have been an internal development. Zilog might still be in business, doing something else."

The machines, and the stories, go on. Here's PC's Limited Turbo PC: "That was Dell before they were called 'Dell,' when [Michael Dell] first moved out of the dorm room." Here's NeXT: "That was Steve Jobs' company when he left Apple, with a new operating system. The computer has achieved cult status, and it also looks really, really cool." It does. Here's an Iris Indigo: "They made Terminator 2 and Jurassic Park -- all the film graphics -- with this: an off-the-shelf mini-computer." Nearby is a Macintosh TV, with a TV tuner: "It's black, perhaps their only black model -- they made and sold it for six months and then canceled the project."

Story after story. Bilstein says he has accumulated most of this marvelous stuff through random donations to this and other Goodwill stores, with perhaps an additional 25% of the collection donated by collectors directly for the museum. The collection grows steadily; a visitor who stopped by last week would newly discover a Magnavox Odyssey, which Bilstein tells me is "the first-ever home video game system, dating from 1972." It was designed by Ralph Baer, who had patented the concept in 1968, and later sold by Magnavox. "Nolan Bushnell saw it at a Magnavox demo in 1972, and was inspired to create Pong, the first ever coin-op arcade machine."

Bilstein's burgeoning success has created its own form of technological obsolescence: He's running out of room. The powers-that-be at Goodwill have thus far been supportive, but they admit they're not exactly in the museum business. Recycling manager Jamey White -- already up to his elbows in to-be-recycled computers of every imaginable variety -- laughs at the prospect, and says maybe one day The Relics of the Past can have their own building. "I'm thinking about approaching corporations," says Bilstein. "Sometime we're going to run out of space. Ideally, we'd like to see a real computer museum in Austin." Maybe there's a dot-com tycoon out there with a pocket full of money -- and a garage full of old computers -- who wants to share both with Alex Bilstein, Goodwill, and the rest of Texas. ![]()