Naturally Nader

Consumer Advocate Mounts Green Party Presidential Campaign

By Robert Bryce, Fri., April 7, 2000

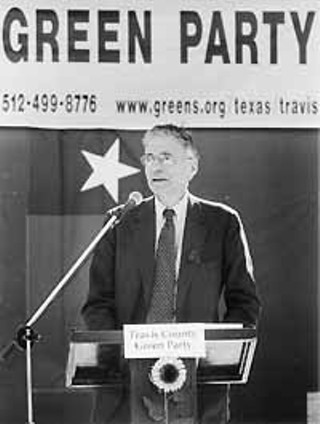

You don't get elected president of the United States by quoting Cicero. You win by showing you look good in a suit, that you can throw a baseball, flip pancakes, and give short, glib answers to questions on predictable issues. You win by raising and spending tens of millions of dollars given to you by wealthy individuals and tens of millions more in soft money garnered with a wink and a nod from corporations and political action committees. You win by cozying up to Elian Gonzalez and by trashing your opponent every day while taking credit for every good thing that happens even if you didn't have anything to do with it. Despite those rather obvious truths, the man who helped put seat belts and airbags in your automobile just can't help himself. Ralph Nader believes that Cicero -- the Roman orator and statesman who said, "Freedom is participation in power" -- was right.

Nader believes it with every fiber in his tall, bony body. And during stump speeches he tosses out Cicero's 2,000-year-old admonition to illustrate his belief that our democracy is faltering. The only way to heal it, he believes, is to reform the American political system. Nader doesn't want "reform" the way George W. Bush and Al Gore want it. That won't be enough. Nader envisions a Martin Luther-type of Reformation, with a capital R. He wants an overhaul of the political system that will allow ordinary citizens to have direct access to their government. Under the Nader Administration, the Catholic, top-down model of politics will be replaced with a Protestant one, where everyone has equal access to the salvation promised by government.

But storming the walls of the Vatican takes money, media attention, and friends. And right now, Nader, 66, who is running as the Green Party candidate, has little money. He's hoping to raise $5 million that will be spent solely on organizing his campaign and its volunteers. By comparison, last week, George W. Bush helped the GOP raise $15 million in a single event. By the time all the votes are counted, Bush will likely have spent 30 times more money than Nader, who is now mounting his third campaign for the White House. In 1992, he ran as a write-in candidate. In 1996, he ran as the Green Party nominee and got 684,000 votes and 2% of the vote in California.

Despite his long history in politics and consumer issues, major media outlets are giving more attention to Melania Knauss than they are to Nader. Knauss, the Slovenian model who used to be Donald Trump's girlfriend, has been the subject of numerous TV and newspaper stories even though neither she nor the egomaniacal Trump are even running for president. Although Nader is getting a fair amount of coverage from small, regional papers, the national press is largely ignoring his candidacy. When he formally announced his candidacy on February 21, the event garnered just 331 words in The New York Times. It wasn't covered at all by The Washington Post even though Nader lives in D.C., and his announcement event was held there.

As for friends, well, Nader doesn't have many who can help push him into the White House. In fact, the opposite appears to be true. Nader began creating powerful enemies in 1965 when he wrote Unsafe at Any Speed, a treatise on the lack of attention to safety by American automakers. Since that time, he has made a career out of attacking the rich and powerful. And they have attacked him in return. Every few years, it seems, another book or article appears that criticizes Nader for his ego, his relationships with trial lawyers, or his workaholic style. In 1990, a lengthy hit piece in Forbes called Nader "unsaintly -- and untrustworthy -- at any speed."

Rooted in Consumerism

Born to Lebanese immigrant parents in Winsted, Connecticut, Nader graduated magna cum laude from Princeton in 1955. From there he went to Harvard Law School. He vaulted into the public arena for good in 1965 when he attacked General Motors' Corvair, a compact car that had a series of safety problems. Unsafe at Any Speed began his decades-long effort to force American automakers to redesign their products and make them safer. His battles with GM also allowed him to create a diverse web of consumer groups. After GM sicced private investigators on him, Nader sued and won a $425,000 settlement that he used to start the first Public Interest Research Group (PIRG). In 1966, he led a fight that forced automakers to put seat belts in all of their cars.

That crusade led to others, including fights to create the Freedom of Information Act and the Clean Air Act. He also helped ban smoking on airline flights and forced airlines to compensate passengers that get bumped from flights that are over-booked. Organizations that he has founded or been involved in creating include Public Citizen, Aviation Consumer Action Project, Center for Auto Safety, Multinational Monitor, and Congressional Accountability Project. He is, without a doubt, the most influential consumer activist of the last 50 years. He is also one of the most peculiar public figures in America. He is often compared to a priest. He has never been married nor had children. If he has a love life, no one knows about it. His hero (and apparently his role model) is baseball player Lou Gehrig, who for decades held the record for playing in the most consecutive games. Nader has never owned a car and he has lived in the same Washington boarding house for years. He is not ugly, nor is he handsome. His suits are decidedly unfashionable. One former associate recently wrote in Salon that Nader has "the look of a man who cuts his hair with kitchen scissors" and that "his idea of great bedtime reading is the Congressional Record." His life is his work and vice versa.

Despite those factors, or maybe because of them, Nader is appealing. Perhaps it's an appeal born of knowing that he doesn't have a chance of winning. Perhaps it's due to his desire to address the issues no one else is talking about, like reforming our political system. Or perhaps it's simply due to his passion, a passion that springs from disgust with the current system. In between bites of kiwi and spoonfuls of hummus during a breakfast interview in Austin a few weeks ago, Nader talked about what he envisions in American democracy. And it looks nothing like the one we have now.

He wants to change the way we eat (by discouraging corporate farming), the way we drink (by cleaning up the nation's waterways), the way we trade (by dropping out of the World Trade Organization), the way politicians run for office (by instituting public funding of campaigns and making TV and radio networks provide free airtime to candidates), the way we invest (by giving shareholders more power to push proxy resolutions), and dozens of other things. It's a radical menu for change at a time when Americans, for the most part, appear to be complacent and fairly happy with the system that we have.

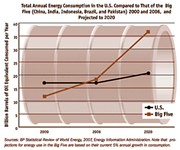

While George Bush favors large increases in military spending, Nader favors demobilization. "That's what we have done throughout our history. When the war was over, the boys came home. Now they don't come home. We are spending $80 billion a year keeping them in Western Europe and Eastern Asia. Why? I haven't discerned any threat from Inner Mongolia or Belo-Russia." What about American presence in the Persian Gulf? "That's to control Mideast oil," replies Nader. "We import 50% of our oil. So it becomes a national security issue. We aren't doing energy conservation. We don't do solar energy. We've had notice of this since '73. Now they say 'look, it's a national security issue.' You have to back up and start the foreign policy issue with energy policy. What ever happened to energy independence?"

Gloom and Doom Predicted

Nader doesn't have much respect for his opponents. Asked the difference between Bush and Al Gore, Nader responds, "The difference is the velocity with which their knees hit the floor when corporations knock on their door."

Nader had particularly harsh words for Bush. If he's elected, Nader predicts, his administration will be marked by "dirty environment, dirty politics and stumbling teleprompter lines, massive expansion of useless military weapons systems, and the further consolidation of the corporatization of every aspect of our society. How's that for starters? But Gore wouldn't do much worse. Or much better." Bush will lose, predicts Nader, and he himself will be the cause. "It's the pinhead factor. He'll defeat himself. Even the way he looks on TV is strange. That's deadly stuff. He's intellectually thin, cognitively thin. I don't think he's going to get any smarter by November."

Nader also lobbed grenades at the vice president. "Gore's a whore," says Nader. "A real whore. He's also a dirty campaigner. The Republicans better realize that." Gore, he adds, is "totally committed to solar energy and to converting the motor vehicle propulsion system, in his book. [Earth in the Balance] Right? Complete surrender. But he learned from Clinton." Despite Gore's flip-flops and his ties to Clinton, Nader predicts Gore will win because the "American people will take a terribly immoral, personally immoral guy if the guy knows how to run the country -- that's why Clinton has such high approval ratings. And that's going to continue. I think Gore has Bush in an incredible corner. Unless something turns around like the Reno Justice Department, Gore will be the next president."

By predicting Gore will win, Nader is tacitly admitting that he won't. Given that he can't win, and knows he can't, why is he even running? "What do you think I am, a quitter?" he replies, half serious and half joking. "Rome wasn't built in a day. We have to win over time," he says. "There are a lot of ways to define winning before an election is won. One is you bring state and local people to run. Second, you bring a lot of people into political activity, which is a very long-range plan. Third, you push a change in the dialogue to concentrate on corporate power in all its ramifications, in the workplace, marketplace, environment, government, childhood exploitation, corporatization of the universities."

Getting on the Ballot

Although Nader hopes to make those issues a part of the presidential race, he has to pass a big hurdle first: He has to get on the ballot. And neither the Democrats or the Republicans are eager to help him, since any votes that go to a third-party candidate are ones that won't go to the major parties. Nader admits that achieving his goal of getting on the ballot in all 50 states won't be easy. In Texas alone, the Green Party must collect about 50,000 signatures. That would be a tall order under the best circumstances. But what makes it even harder is that all of the valid signatures must be from people who did not vote in the March 14 primary. Nader seems unfazed. Here in Texas, he says, getting the signatures "should be child's play."

To fire up his supporters, Nader reminded listeners during his speeches in Austin that the Republican Party wasn't formed until 1854, and that in just six years, the GOP won the White House with the anti-slavery platform carried by Abraham Lincoln. Nader knows his history. But he doesn't mention that the Republicans were only able to form because the Whig party disintegrated and because the Democrats and the Know-Nothings were in turmoil. The Green Party faces a far different situation. It doesn't have a single, decisive issue around which it can rally. And it must fight the two long-entrenched parties if it is to make any headway.

Nader, who has always liked his role as the underdog, doesn't seem to mind. He likes the spotlight, and it's clear his passion for the fight -- even after more than 35 years -- is undiminished. So now that he's officially a senior citizen who could quietly retire and leave the battles to someone else, what is it that keeps him so motivated? What's the source of his ever-present indignation? The answer comes quickly. "Injustice," he replies. "Do you need anything else?"

It's the kind of answer that would make Cicero proud. But then, Cicero, who spoke out in favor of republican ideals during the civil wars that destroyed the republic of Rome, was a sucker for lost causes. He was executed in 43 B.C. ![]()

Got something to say on the subject? Send a letter to the editor.