The Last Fool of Chelm

How Nathan Englander Survives His New Fame

By David Garza, Fri., Dec. 3, 1999

Nathan Englander has taken the pulpit. A small crowd is gathered in the synagogue on a cool Monday night during the 16th Annual Austin Jewish Book Fair, and right at the altar, just below the massive stone tablets declaring the laws of the holy, straight to the right of the representations of fire, and before the eyes of the town, the young writer opens his book and reads -- not from the scriptures -- but from For the Relief of Unbearable Urges, a collection of short stories published by Knopf. "Reb Kringle," he says, announcing the funniest story in his book, the tale of a cranky old Jew who is whipped into working as shopping mall Santa by his wife. But despite all the laughter as the unlikely Santa loses his cool and goes berserk in a shop full of gentiles, the questions after the reading are heavy and strangely important.

"How should we teach Judaism to our secular children?" asks a woman from the audience. A few minutes later, another audience member shares her memories of the day Benjamin Netanyahu slipped into power. Though he is just 29, and though he has still only published one collection of nine short stories, Nathan Englander has instantly become one of those most rare public figures in our society: the writer whose opinions are heatedly sought, meticulously recorded, and taken directly to heart. And while it's happened elsewhere that poets have become dictators and playwrights have staged whole fiscal policies, it seems sweetly bizarre that the role of the artist has changed just a bit, in this country anyway, to accommodate this young and talented writer.

"I could be running Czechoslovakia," he jokes the next day. And with the way people follow his words, maybe he should.

That's not to say that Englander takes himself nearly as seriously as everyone else does. He calls himself "Smoky the Bear of Secular Judaism, doing secular outreach across the whole country" and is frank in describing how important -- or unimportant -- his background in Orthodoxy and ties to the Jewish communities are to his writing and literature in general.

"This is the bottom line: I wrote a book, and this is the book I read from. I read whatever I want from it, I surely don't edit because of surroundings, and if that's the room we're using, well -- I read in a church in Manchester, England, in a good Church of England church, and I read in a synagogue in Austin."

Still, Englander has spent much of the year giving such readings and trying to answer these sizable questions from audiences in Germany and Holland, Scotland and Wales, and all over the U.S. He describes the nearly absurd events of the past year, in which he has been anointed by media outlets from The New Yorker to Entertainment Weekly, as occurrences and duties wholly extraneous to his work as a writer: "It's not about me. Or it is about me, and it's not." While he is always polite and clearly engaged by the questions and stories fans present to him, it's no whispered secret that he'd like to lock up his doors for a few days and get back to writing his forthcoming novel.

"It's all for good," he says. "I worked so many years on this book and now you want me to read from it for a while? What's my main purpose is to write; this has nothing to do with writing. The only element, maybe, is that reading the stories, it's good for me to hear them, it's good for me to see the readers as people and watch them reacting to fiction. You can learn from that. But promotion and touring the book has nothing to do with what I do, basically. But I'm more than happy to do it."

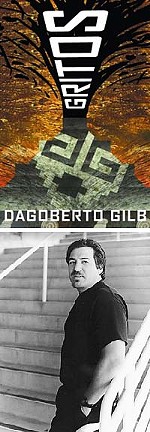

For those who have never studied the stories that have made Englander famous, it surely comes as a shock that the praise he receives is so unanimous and universal. "This isn't supposed to happen. It isn't supposed to happen to a collection of stories, and it surely isn't supposed to happen to me," he says. But readers have not been reacting to a simple spinner of tales who makes clever jokes about religion (though he smiles as he tells the audience in the synagogue that he almost called his book Those Crazy Jews). The stories in For the Relief of Unbearable Urges are rich and varied in their reach and in their tone. While they have been praised for their humor and irreverence, there is always a deep and sometimes tragic respect for the Jewish tradition in every line of the text. What is often overlooked is that what makes the book succeed in its moments of triumph is its unwavering reverence for history and human emotion, Jewish or not.

"Whether Ruchama [the main character of his story "The Wig"] is wrestling with wearing a wig or not affects a reader that's completely separate from that [Orthodox] world in one way, whereas it might really be an issue to someone else about their own [life]," he says. "It can be in general, say, an issue about a woman's freedom or freedom in general or individual choices of modesty or vanity or beauty, but if you go into a specific community, it can be like, "Someone's wearing a wig, and should I wear it? Or is this guy saying that I shouldn't?' On that level I'm not prescribing anything, but when I show up in certain places, that seems to be on the table."

Also on the table is his determination to do something seemingly impossible: to write convincingly from the perspective of both mystical and martyred Jews who have lived in distinct parts of the world during distinct historical periods while preserving himself as a detached and secular individual. Strangely enough, Englander feels most comfortable working at this ambitious goal in the Holy Land itself. Since moving to Jerusalem in 1996, one week after graduating from the Iowa Writers' Workshop, he has spent much of his time surviving the everyday political turmoil, revising his manuscripts, and despite the hefty sums he's amassed, forgetting to pay his own bills (when asked, he claims that the Eleventh Commandment should be "Thou shalt balance your checkbook"). Having arrived in the city with broken Hebrew and some Aramaic, the stay has been filled with strange learnings.

"The more I fit in, the more I'm part of the other," he says.

Whether that "other" refers to his secular identity, his Americanness, or his inner self, the lessons of Jerusalem have served his text well. Early in the book, one of his characters is faced with the question, "Why write at all when your readers have been turned to ash?" It's a question reminiscent of the theorist Theodor Adorno scolding the poets who tried to dignify Auschwitz, and a challenge, of course, to the nature and abilities of literature to serve emotional, aesthetic, and, most importantly, historical functions. Nathan Englander almost blushes when an audience member asks if he could ever write fiction in Hebrew. What he can not admit is that, using his own English language, he gracefully adds to the sacred and historical Jewish tradition in his pioneer way.

Take, for instance, his story "The Tumblers." Retelling the traditional myth of the fools of the Village of Chelm, Englander places his characters in the midst of the Second World War and tests their unconventional wisdom against the unbearably strong arm of the Reich. As he tells of the changes that are made in the village as they are moved into a ghetto and later forced onto a camp-bound train, he performs a stunning subversion of the historical Nazi corruption of language: "-- They called their aches "mother's milk,' and darkness became "freedom'; filth they referred to as "hope.'" The echo in these lines of the famous maxims branded on the gates of death camps, "Work shall set you free," and so forth, are horrifying in their strenuous struggle between death and life.

In order to escape the death that awaits them, the fools of Chelm must pretend to be circus acrobats, and they have only a few days to learn their routine, perfect it, and juggle and jump for the masters themselves. Mendel, the leader of the group, must learn the tricks of this outside world and, to an extent, become one of these others as well as he can. Only then can he share the secrets of tumbling, and of survival, with his unbearably tragic boxcar of Jews. Thanks to the clever and goofy, seductive Mendel, they come up with a show that is executed with incredible heart and with beauty, if not precision. With or without the fame and attention, it's easy enough to see so much of Mendel in Englander's eyes, and this impossible stretching of limbs in his words. ![]()