What the Right Hand Is Doing

Harry Anderson, the Left-Handed League, and Me

By Turk Pipkin, Fri., Sept. 3, 1999

Saturday evening, September 4, magician turned sitcom star (and former Austinite) Harry Anderson will be joined by Turk Pipkin, Mike Caveney, and Martin Lewis for the 20-year reunion of the Left-Handed League at Palmer Auditorium.

Twenty-five years ago, when Austin was one of the best places on earth to experience a cosmic collision of fates, I drove my old bread truck-turned-hippie mobile down to Armadillo World Headquarters and told the folks in charge I should be their opening act that very night. But wouldn't you know it, they already had an opener, some street magician named Harry Anderson, with whom I soon struck up a conversation, a joint, and a lifelong friendship. I suppose it was inevitable. We were two of only a few successful street performers in the country -- I was a lousy magician and Harry couldn't juggle to save his life (which meant we didn't have to compete against each other) -- and both of us were eager to move on to bigger and better things.

A magician since his early childhood, with a mother Harry readily admitted was known to turn a trick or two herself, Harry hit the streets early, fleecing San Francisco tourists with the three shell game: "Lookee, lookee, lookee, it's the one in the middle -- which one is it now?" Sufficiently game to pull off this classic scam, Harry still wasn't wise enough to know that absolutely no one runs a shell game or three card monte without a full gang of accomplices: look-outs watching for cops, shills paid to juice up the action, and, most important, some muscle to chill out any serious beefs.

Going solo, of course, eventually ended the way it will, with a guy so pissed that he'd lost a couple of twenties and looked like a fool to boot that he sucker-punched Harry, breaking his jaw, which remained wired shut for months afterward. An extended liquid diet consisting (I've always imagined) mostly of Southern Comfort led Harry to the conclusion that accepting donations might be healthier than simply taking them.

By the time we met, I'd had some travails of my own, including a three-year encounter with an unlucky draft number and the U.S. Navy, staying sane by jumping ship whenever a good opportunity arose to pass the hat. If the Grateful Dead (or nearly anyone great) was in town, I'd work the lines waiting to get into the concert. One night in L.A., after talking my way into an opening spot at an Emmylou Harris/Leon Redbone concert, Emmylou suggested that I come down to the first-ever rock concerts at Dodger Stadium and juggle somewhere between her set, the Eagles, and Elton John.

With no more credentials than her tip, the next day I made my way past a half-dozen security checkpoints and was soon doing my torch-juggling act in front of 70,000 screaming hippies. Since my long-ignored conscientious objector claim with the Navy had recently left me permanently AWOL and prominent in the files of every law enforcement agency in the country, I was a little worried when they introduced me with my real name. The promoter, on the other hand, was more concerned with the fact that I simply didn't belong up there. When they finally kicked me off the stage, I waded into the crowd and performed first on the pitcher's mound, then on both team dugouts and the warning track. At some point I met one of those prototypical California beach chicks who offered to help me pass the hat, which, since I was performing a piece of clowning about a guy rolling and smoking a 15-foot doobie, always came back almost as filled with dope as it was with money.

Parked at the beach that Sunday evening with my new surfer girlfriend, we counted over a thousand bucks in small bills and change, a couple of hundred multicolored mystery joints, and enough questionable acid and pharmaceuticals to light up Santa Monica.

The only thing all that has to do with Harry Anderson is that I used the dough to hire a lawyer who convinced the Navy that I was legally entitled to an honorable discharge, so that I soon found myself in Austin, where Harry and I met and became partners, probably because it was destiny, but possibly because I still had a lot of mystery joints hidden beneath the floor of my van.

A few months after thatfirst encounter, Harry asked me if I wanted to be his partner. I didn't know exactly what he meant by the term "partner," but I knew a good deal when I heard one. So for 25 years we've been partners, and I'm still not sure what it means.

It was uncanny how often we'd bump into each other in our respective driving and performing pilgrimages from the Gulf Coast to the Northwest. One year Harry made a quick trip to New Orleans for Mardi Gras where he spent three days in the drunk tank for passing the hat, an experience he must not have minded much since he soon moved to New Orleans. Not having his address, I simply drove down, walked into the first bar that caught my eye -- the Alpenhof just off Jackson Square -- and found Harry drinking a Dixie beer and showing off for the waitress.

It did not take us long to tire of passing the hat, but since the street was the hardest gig going, it was a simple matter to switch to clubs, theatres or college union shows that actually told you how much you were going to make before the show.

Soon Harry took up residence back in Austin at the old Alamo Hotel, living next door to LBJ's nearly forgotten brother, Sam Houston Johnson, who often greeted us in his smoking jacket as he let Zip the elevator man bring a bottle to his room.

Having sold my step van to pay for an extended trip to Europe (where the street gigs were lucrative but the European girls less susceptible to my bullshit), I was back in Austin myself, living in West Campus with the Art & Sausages gonzo political gang. Nearly every midnight I could be found at the old Steak & Egg Kitchen on 19th Street, where Harry and I drank coffee and talked endlessly about comedy and magic, movies and theatre.

Harry had recently taken a happy hour gig doing close-up magic at Mike & Charlie's Bar, so his hands and mind were constantly working -- stacking cards and loading dice as he devised new ways to put the shuck on the same overflow crowd of regulars who came by every night to see what he'd dreamed up.

At some point, Harry decided he'd created or learned 24 hours of card magic, so Michel Jaroschy (bless his soul) booked him into the Gaslight Theater (later the Capital City Playhouse, now Fadó, a sad substitute indeed), where Harry performed 24 hours of card magic without repeating a trick. As his "partner," I spent the whole 24 hours gathering huge piles of spent decks and sorting them into blues and reds, Bicycles and Aviators, marking or stacking them the best I could for whatever tricks I thought might be next.

In the meantime, I'd become the semi-regular opening act at the Armadillo, working with Spyro Gyra, Talking Heads, Freddie King, and Commander Cody, and eventually inheriting the New Year's Eve gig after manager Bobby Hederman put Harry onstage at five minutes till midnight in front of a riotous partying crowd, then later had the nerve to tell Harry that he, "didn't go over too well."

Months would pass without our seeing each other -- I'd be in Italy or Harry in Ashland at the Oregon Shakespeare Festival -- then we'd hook back up and trade notes on what we'd learned. One trick to writing lots of new material, we found, was to book a gig -- say a two-hour, one-man show at Capital City Playhouse -- that forced us to write like madmen. I figured if Harry could pull it off, then so could I. It wasn't until years later that I realized he was thinking the same thing about me.

After an extended trip to Great Britain, Harry returned to Austin and told me that he was moving to Hollywood, where he planned to become a television star. I thought he was somewhere between overly optimistic and just plain nuts and wished him luck.

Within months I was camped out on the futon sofa of his one-bedroom apartment, ideally situated in a drug-infested neighborhood just a block off Hollywood Boulevard. Every weekday began with a ritual gathering around a tiny 5" television screen watching David Letterman's short-lived but brilliant morning show. Harry introduced me to his clubhouse, the nearby Magic Castle, where some of the greatest magical minds of our century were happily spending their waning years passing on their trade secrets to eager youngsters like ourselves.

Soon I was living in my own ratty Hollywood apartment, performing at comedy clubs, learning what I could, and chipping in my two cents worth as Harry created a smart-ass stage persona named Harry the Hat. Harry the Hat took no prisoners and became infamous for acts like eating a live guinea pig or shoving a needle through his arm, swearing all the while that it was an illusion -- "Like economic recovery," he'd say -- but, oh what an illusion when that bright red blood came trickling down his arm!

One day we drove out to Azusa, California, to do a little shopping at an old-fashioned illusion factory called Owen Magic, where the owner showed us a vintage gambler's holdout -- a piece of intricate brass machining with which a card player could surreptitiously hook a hidden wire from one knee to the other and switch an ace from his sleeve to his hand.

"They took that one off a body that washed up years ago on Santa Monica beach," Les told us.

Harry had to have it. Driving back home, we hustled to think of how to explain to his wife that he'd just spent their entire $800 savings on a useless gambling prop. Panic is a fine inspiration. By the time we reached Hollywood, Harry had written an entire new act in which the hold-out was the absurdly impossible explanation for how he'd performed a torn and restored bill trick. Taking off his jacket and dropping his pants, he'd show how he'd hooked his knees together and switched the money with the hold-out. The point, of course, was that his pants were down and his boxer shorts ridiculous. Audiences loved it, and the next time I turned on a TV, Harry was on Saturday Night Live getting famous.

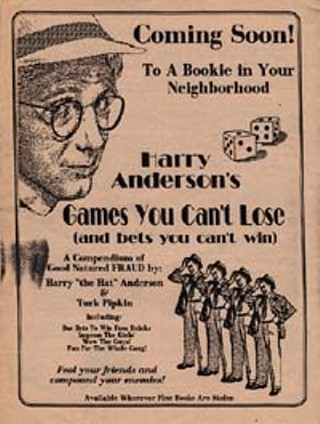

As Harry's "partner" I didn't share in all his success, but I did okay. When Harry the Hat was made a semi-regular cast member in a new NBC sitcom called Cheers, he managed to sneak me in the door as the warm-up act for the tapings. We did our goofy pickpocket act on The Merv Griffin Show and on the first Comic Relief, and we co-wrote a Harry the Hat book that sold better than any of the seven books I've published since.

The day following Harry's amazing debut on Cheers, the sitcom pilot scripts came pouring into his house. Taking it upon myself to wade through them in search of something worthwhile, one day I pulled a script called Night Court out of the trash, read about 20 pages and told Harry he'd better take a look at it. Harry took a hard look, got the part, and was soon living in Michael Landon's former Spanish mansion, which Harry renamed Casa Residuales.

Sometimes we took our partnership a little too seriously. When Christy and I got married in Austin, Harry was our best man. Then two days later, Harry and I embarked on a nationwide club and concert tour, including a honeymoon stop at Niagara Falls where we had our picture taken together on the honeymoon boat, the Maid of the Mist. I sent the picture to my new bride; for some reason she didn't leave me.

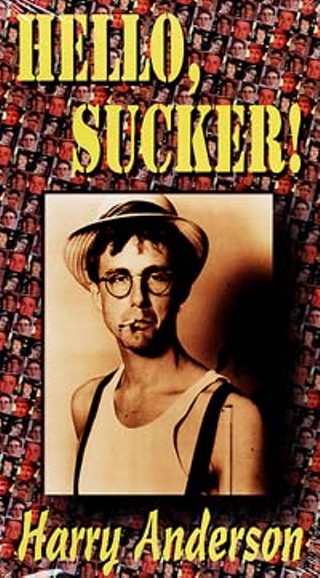

While we were touring, I was his opening act and his road and stage manager (and usually managed to be good at two of the three). In our spare time, we concocted a one-hour Harry the Hat special for Showtime called Hello, Sucker. At Harry's insistence, I was a co-starring second banana, and though the show turned out great, it was obvious I wasn't going to repeat Harry's successes on TV. No matter, I'd assimilated enough television knowledge from being around my partner to start me on a 15-year string of network writing gigs.

Through it all, one of our most gloriously ridiculous endeavors was Harry's company of wiseguys, The Left-Handed League. In the early Eighties, we were Harry the Hat's gang -- magicians, mentalists, pickpockets -- we even had a beautiful exotic dancer, Katlyn "Le Strange," who doubled as a practicing witch. Ventriloquist Jay Johnson -- who played Chuck and his dummy Bob on the television series Soap -- was a founding member. Likewise with some of the finest and most irreverent magicians in the world: Mike Caveney, Martin Lewis, and magician and mime Tina Lenert.

All of us were at a period in our lives when we seemed to have all the performance gigs we needed. But one more show in a nightclub just like the 200 you'd already done that year held little interest compared to gathering around Harry's pool table for long hours of everyone talking at once about new ways -- as Pinky's friend the Brain would put it so many years later -- "to take over the world." The idea was to convince the world (of show bizness, anyway) that we could solve anyone's problems through the clever application of Left-handed ingenuity.

Oddly enough, like our fearless leader Harry, everyone else was also left-handed -- except for myself who, being a juggler, was explained as either ambidextrous or left-brained (or perhaps I was the Left-Handed League's right-hand man). Still, the group's name was based mostly on our left-handed methods. Truthfully, no one knew what to think of us, and that, of course, was our greatest strength.

Periodically we'd stage a weird and wonderful Halloween or New Year's show, but our chief celebrity rested in our claim to have never failed to solve any problem or create any deception required. (Certainly our problem-solving skills were unique. Martin Lewis' self-described motto in the league was "The British Cheat." But when his business cards came back from the printer reading "The British Chest," Martin solved the problem by declaring the typo an improvement.)

"Mental and Physical Phenomena, Psychic and Mystic manifestations, Locks and Pockets Picked," read a pitch sheet I wrote to describe our collective talents. "Sophists and Pharisees undone. The Boundaries of Reality Godlessly Gerrymandered." The phrases just kept coming, I couldn't stop.

The amazing thing was that Hollywood actually fell for this weighty load of baloney. HBO optioned a Left-Handed League movie based on a play written by Harry; my pal Bud Shrake and his pal Dan Jenkins sold us to a studio to create a third-act sting for a con movie they were writing.

"We told them the truth and they fell for it," became one of Harry's favorite sayings.

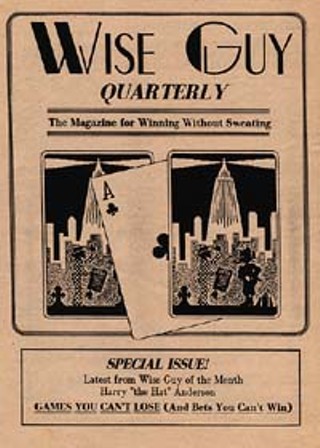

The pinnacle of our gall, if I can be so bold, occurred in 1982 when the League decided that the world of magic was ripe for parody, especially the trade's fatuous magic magazines, only a couple of paragraphs of which would put anyone but a stone cold magic geek into a lifelong coma. Since the most widely read of these was Genie Magazine, it was only a small leap of logic to write and publish Wenii, a merciless lampoon of Genie in which a large amount of the humor was derived from dick and weenie jokes. In Wenii the father of modern magic was not Harry Houdini, but Harry Hujuini, the Oscar Mayer Weinermobile was pictured throughout, and the reviewed magic tricks were rated with magician's wands ranging from stiff to limp. If it sounds sophomoric, it was meant to be (or so the League claimed). If we had properly skewered the dicks of the magic world, then we figured the world of magic would be better off for it.

To this day, my all-time favorite piece of comedy writing is magician Mike Caveney's fictitious (but all too real) review in Wenii of the Southern California Unified Magican's (S.C.U.M.) Conference in Monrovia, California. The hit of the show, according to Mike, was a sightless mentalist named Eddie Nomber who covered his eyes with two metal washers, Scotch tape, glazed doughnuts, and 45 rpm records and wrapped his whole head in Saran Wrap.

"Am I holding a pair of glasses?" asked his assistant who was wandering through the audience testing his skills.

"Yes," replied Mr. Nomber.

Item after item was held aloft and Eddie never failed with the correct response. Even when she tried to stump him: "A lawnmower?" "No." "A cattle prod?" "No." "A comb?" "Yes."

Finally she asked, "Am I holding up a S.C.U.M. bag?" and Eddie responded, "You are surrounded by S.C.U.M. bags!" The audience roared its approval.

If you're wondering why you never heard of the Left-Handed League, it could be because we knew we'd never top Wenii. Our last official League performance was at a magic convention in 1986, which means we've had a little time to rehearse all the new material.

And speaking of magic conventions, it just so happens that the Texas Association of Magicians is having their annual confab in Austin this Labor Day weekend. As a part of their "Magic Weekend," on Saturday, September 4, the Left-Handed League will be performing our 20th anniversary reunion show at Palmer Auditorium. No word yet on whether any S.CU.M. bags will be in attendance, but our pals and former Leaguers Martin Lewis, "the British Chest," and Mike Caveney will be performing some killer magic, and I'll be faking it the way I have all along.

Most of the crowd will come to see Harry. I don't know whether he'll be dropping trou, "eating the pig," or shoving a needle through his arm for your entertainment, but I do know that it's his first show in Austin in 15 years (and nearly his first visit since we both had vasectomies [by local urologist Dick Chop], which I wrote about for Playboy and which I can assure you was taking the partnership thing a bit too far).

Palmer Auditorium is hardly the same as the Armadillo where Harry and I met, but I'm taking comfort in the fact that it's right across the street from the spot where my life took a left-handed turn for the better.

What more can you ask? ![]()